Everyone is ready to go fight anyone, anywhere

– Douglas Coupland, Shamon Basar

Reflections on

Fields of Practice

When I think of globalisation and its effects on the creative, artistic, and crafts world I am reminded of Robert Esdaile’s note to Hector Stentsadvold, rector of the National College of Applied Art and Craft when he lamented the fact that our material culture was been transformed through ‘a steadily increasing the number of mass-produced articles of foreign design and origin.’ (Ref: Funnarsjaa, Arkitekturleksikon, 729).

Crucially though, Esdaile’s idea of local design solutions was married to an appreciation of the global perspective fostered by ecological thinking in a response to the environmental crisis, all of which was penned in 1966. Looking at this position, you could draw a conclusion that he was preempting the pre-covid-19 trend of think globally, act locally a point touch upon a number of times by Harriet Ferguson when she discusses Apples, Karma Cola, and Airbnb’s approach to creating global brands that have their own cultural references that reinforce the markets they find themselves in and yet this work is still a continued use of perspective rooted in Euro-American design edicts. In another way, when Simon Mailchipp mentions that ‘Globalisation is an unstoppable force’ we could view the ‘Think Globally, Act Locally’ as just a natural progression of what was an unstoppable march that has allowed creative studios and designers to position themselves anywhere in the world, work at a local level and produce work that can then be viewed and commissioned globally.

But the question has to be asked, through this process, are creative studios and designers just feeding into an outdated economic model and what is the true value of their output if, for example, an English agency can be commissioned to work on a tampon product for the Chinese market. Yes, it encourages greater collaboration and a bigger idea and canvas but have designers failed to acknowledge that within this they are just feeding onto an economic model that has been turned on its’s head by a global pandemic, a rise in nationalistic tendencies, and a 'failed’ Brexit all while slowly (sic) poisoning the planet and that perhaps the term ‘Think Globally, Act Locally’ should now be viewed as ‘Think Locally, Act Globally.

As Victor Papaenek notes in The Green Imperative – ‘The easiest way to save resources and energy and to reduce wastes is to use less. This means consuming less, buying less, being Green, making do with what we already have – establishing an imperative to rid ourselves of all the unnecessary gadgets and duplication that so hideously clutter our lives…’ (Ref: The Green Imperative, Victor Papanek) Not a particularly nice lens to look through as designers when all we want to do is embrace global culture and connectivity. But if I look at Josephs's idea of ‘Decolonising the Curriculum’, perhaps we could do the same in the wider graphic design world and stop focusing on the global opportunities and start focusing on the differences we can make in the here and now.

Further Thought:

It’s interesting to note the prevalence of a western patriarchal mind-set when listening to the designers speak about their work, noting Regular Practices almost pre-colonial lamenting that ‘visual culture has become a little bit more uniform across the world.’ It’s very easy for white males, and I include myself in this to throw out such lip service statements without bringing in a wider discussion about culture and cultural dimensions in design. Perhaps back again to Joesph’s statement on ‘Decolonising the Curriculum’ we should perhaps tart and acknowledge that ‘the lack of appropriate culturally inclusive course content or any traditional knowledge within design curricula contributes to the displacement of students who o not identify with the hegemony or homogeneity of the Eurocentric or Euro-American tenets principally assimilated through modernist edicts.’

(Ref: Design Struggles – Intersetciong Histories, Pedagogies, and Perspectives, Claudia Mareis & Nina Paim).

D&AD

Graphic Design – one of the most persuasive mediums with which culture is engaged. It allows us to set idea-driven and intention-guided specifications and implement them through the use of colour, type, material section, form, and function. As noted by Audrey Bennet in ‘Design Studies’ – ‘design is a democratic practice that depends on local participation (or global considering the context of the above argument) in all aspects of the cycle, and is acutely responsive to a wider range of design performance requirements demanded by the unique situations occurring within the cultural context.’

So how does the idea of D&AD generic categorisation align with the above and by siloing ourselves do we limit the potential of our creative output? First, I’ve always viewed the categorisation of design as well the terminology employed as a purely economic necessity in helping to define, navigate and silo who and what we are as designers and the services and tangible outputs we can provide to a business or organisation. But do we then run the risk of defining our industry as a purely economic driven model that is just another “service’ industry and fail to acknowledge the depth and breadth of ideas and solutions we can offer beyond brand, digital, product, etc.

Perhaps this is why Made Thought strives for when they say ‘They Create Desire’, though does this not in itself again limit the scope of the work produced by positioning the agency firmly in the service of those who wish to create desire, eg, luxury fashion brands. Perhaps the same could be then said of OK–RM who create ‘Art Direction + Design’ but by using the word art-direction and design, followed by art, culture, and commerce, they again appeal to a niche market for whom art-direction is a tangible and lauded output, eg, luxury fashion brands.

This is where I see the D&AD struggle with so many categorisations that looks to represent the breadth and depth of a field that can’t even categorise itself. If agencies and designers are continually changing the language around themselves then the D&AD run the risk of adding even more categories to its already bloated repertoire.

So if we are to jump back to the idea of setting idea-driven and intention guided specifications perhaps we should look more at the idea of ‘The Self’ when looking to define the categories we fall into, perhaps, playfully and with a nod to the idea of Danial Kaufmanns ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’, should we not perhaps look towards terminology or copy that encompasses storytelling devices and avoid clicked soundbites. Or perhaps we should not even be asking the question of what design is, perhaps within the context of our understanding of our current place and predicament on this planet, we should be asking what the idea of the ‘Self’ is in the design we produce and what is the value of that design output for both ourselves and the planet?

Or perhaps we could just simply ignore the categorisation and self-labeling thing and revert back to the idea of just been creative or in even simpler terms, to borrow a term from Richard Senentt, simply be a Craftsperson.

A morphing into something else in an accelerated cultural landscape.

Further Thought:

We cannot talk about Graphic Design and categorisation without acknowledging the influence of Social Media on the form and the influence it has had on the homogenisation of design where designers and agencies look to ‘score’ points through overly perfected design solutions and Instagram-worthy content that look to reward the ego of the designer/ agency rather than provide a tangible design solution. This ultimately will have a direct effect as categories start to blur as designers and agencies look to outscore each other by showcasing a neverending cross-disciplinary output that cannibalise each other. As I like to refer to its as ‘Dysmorphia of the soul’.

Final outcome

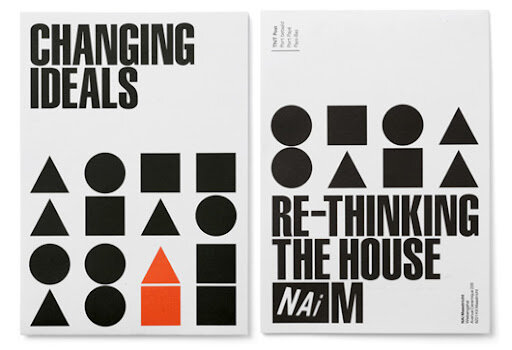

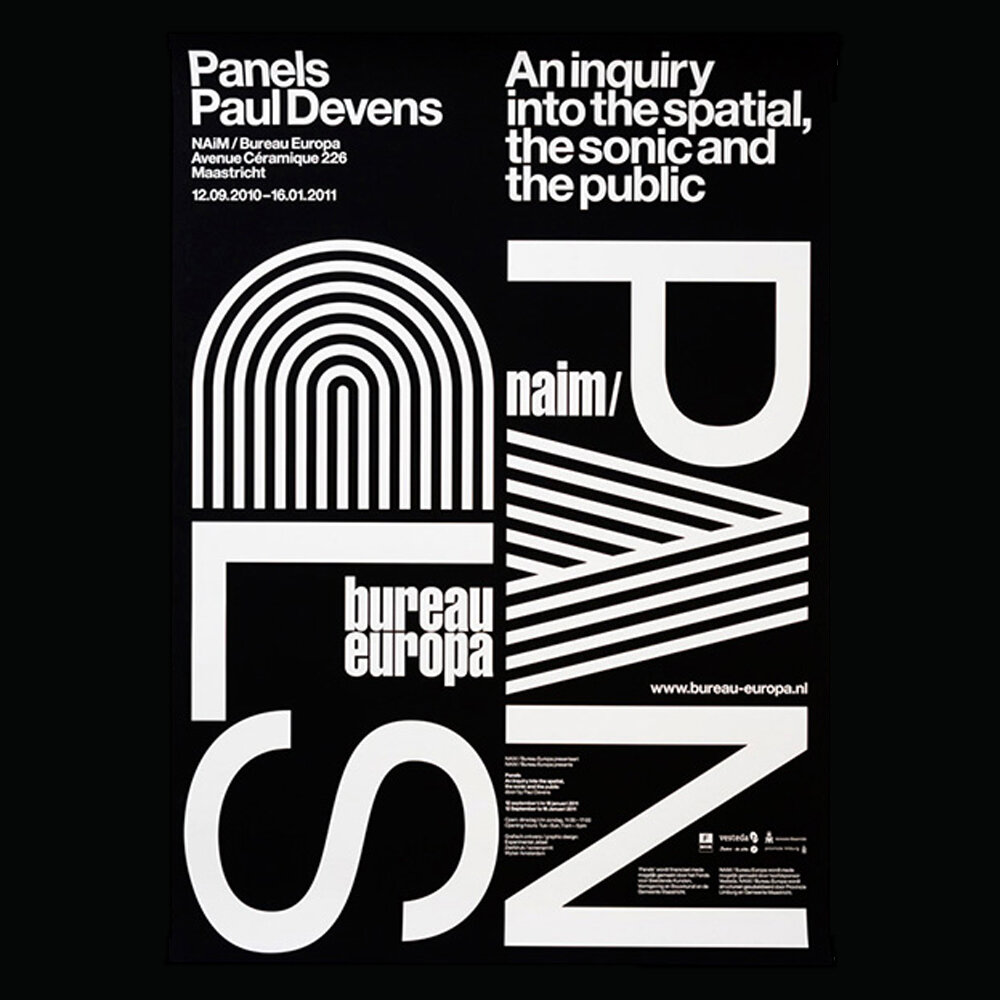

For the editorial piece, I approached the design through the lens of producing a clean editorial somewhat modernist in nature. that relies on a typographic hierarchy married to a strongly gridded layout. The use of Diatype and Times New Roman as logical pairs help to create a sense of a curated rhythm with the graphic device imposing a visual element that plays on the idea of a singularity morphing, an idea explored further in the editorial.

Grid and baseline

Typography

Final editorial Spread (641 words)

Designism

(Excercise 2)

Reflecting on the categories of Graphic Design, it struck me that there is a harmonisation to a degree of the practice through the inherent use of silos to fit the industry into. I then thought of a line I read in The Extreme Self where it states that... All -isms start with some harmonization (sic) of a zealous crowd. This got me thinking that the field of graphic design and its cohorts could be viewed as a zealous crowd. And if we’re to look at the harmonisation we could construct a new term called ‘Designism’ which reinforces the absurdity of forced harmonisation and categorisation.

Further Thought:

I reference Experimental Jestest a lot, not just because of their exemplary design output but also due to the philosophies they adhere to. When exploring the idea of categories and the terms designers and studios put on themselves in reminded mat I also preferred Jetset’s idea of viewing themselves as a band – the idea of a small group of people operating as one unit. By adhering to this heretical structure it allows them to construct a socioeconomic unit that dispenses with the notion of hierarchy and categorisation.

Secondly, I’ve always been intrigued by the artistic representation of Malevich's Black Square and the larger and more universal leap forward represented by the painting that is viewed as a break between representational painting and abstract painting—a complex transition, one which has parallels to the reductionist approach of categorisation to the singular term of Designism.

Initial Sketch 1

Sketch 2 before photoshop

The Wall

Interaction with Shiina Araki

‘The best design and design practice relies on a continuing involvement of both the designer and the community he engages with (craft). The artist is more focused on the idea of the self and the expression of that self towards community. Traditionally artists and designers (nee craftspersons) would of been viewed as one and the same but as knowledge capital grew it allowed the economic value (of a guild) to separate the art and the craft. (Richard Sennets writings in The Craftsman, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2008/feb/09/society). I would agree and argue that these lines are starting to blur more especially in the digital age where the skillset required to allow anyone to produce 'art' and gives permission to design(ers) to apply their creative thinking in a more abstract and self-informed way. Or in the example of someone like the urban designer Theaster Gates, perhaps the designer can merely define themselves as an artist for more strategic purposes, eg, the pursuit of social-economic benefit to help him fund his community housing program in Chicago (full circle? the Craftsman (nee Artist)) benefiting the community)’.

Feedback to Adam Dellou

’The tactile element was definitely a part of the reason that people preferred vinyl over CDS, mores in the record itself (the grooves) rather than the packaging as I believe that packaging of CDS was more innovative than the majority of vinyl records (former record shop owner here!). See Farrow's world for Spiritualized for example where the format tended itself beautifully to the idea of medical. packaging or flouro plastics.’

Feedback to Wes Trimble

’Nice selection of wordsmithery Wes. I'm a believer in what you said about Made Thought on your blog that the looseness of their linguistic approach (copy) allows them to declassify themselves and by extension 'position' themselves across multiple disciplines. My criticism is that this is easier to do at scale and weight than it is for smaller agencies/ freelancers where the focus is on specialisms to help maintain focus. Moreover, though, this again can be limiting if you believe that design is more than just a styling tool and has the potential to make useful contributions to society, it then follows that we need a broader (looser) language to help define what we do. Perhaps some of these words explored could help define that language’.

Reflection

Week 3 proved difficult and was finally completed toward the end of the term due to both work constraints and the fact that having been part of the industry for so long I couldn’t get my head into critically analysing the industry. Perhaps also the fact that I have moved away from agency models and into a space where I was a “creative Consultant’ also fed into my own desire to not pigeon hole not only others but myself when I had worked so hard to separate the ‘Self’ from the egotistical idea of Self which came with been a “creative’ – One to ponder as I move through the MA.

References

(Ref: The Green Imperative, Victor Papanek)

(Ref: Danial Kaufmanns ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’)

(Ref: Richard Sennet ‘The Craftsman’)

(Ref: Audrey Bennet ‘Design Studies’ )

(Ref: Design Struggles – Intersetciong Histories, Pedagogies, and Perspectives, Claudia Mareis & Nina Paim)

(Ref: The Extreme Self. Basar/Coupland/Obrist)